In the past, I assigned a couple essays each quarter, and my strong writers did fine, turning in well-written essays on the due date. My struggling writers, however, had a much more difficult time. Every step took longer, and they were lucky to finish their first draft on the due date. They would turn in an almost-finished essay, be content with a mediocre grade, and ignore my comments, ready to repeat the process a couple weeks later on the next essay.

The worst part of this pattern is that my struggling

writers never learned edit their work. Henry Kissinger once said that, “Good writing is good rewriting,” and Ernest Hemingway wrote, “There is no writing, just rewriting.” Proofreading, correcting, and publishing essays is more important for struggling writers than it is for strong writers since strong writers naturally communicate in grammatically correct, nice sounding sentences.

So this year, I will assess student writing less like a school project and more like a tae kwon do studio. I'm no expert - I only studied tae kwon do for three years before I had children - but I like the systems of belts that represent achievement. Martial artists must test In order to progress to the next belt, show that they have mastered the skills of the previous belt before graduating to the next belt.

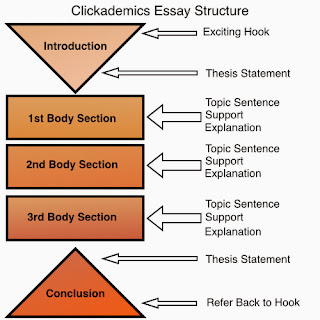

This year, my students must master the first steps in writing before progressing to the next. For instance, a “yellow belt” student will write a complete first draft before moving on to “green belt.” The student must have a complete introductory paragraph, perfect thesis statement, and well-developed body paragraphs in the first draft before I will approve her to start editing as a green belt. Most importantly, she must complete all of the steps of editing - especially incorporating my comments - before starting the outline of the second essay, which is the difference between the green belt and the orange belt.

It was hard for me when I realized that at the end of the quarter, some students would only complete one and a half essays while others would complete three. But outside of school, everyone's expected to learn at a different pace, and we don't move on until we have finished the earlier steps. One of my struggling writers might complete fewer essays, but he will have fully edited and perfected the once he did write, which is a more valuable learning experience than almost finishing three essays. In the end, that student might get the same mediocre grade for writing, but at least he has learned skills that will help him do better next time.

This idea did not come from watching a martial arts movie or learning tae kwon do. It came to me while at a faculty meeting before the first day of school. Our administrator asked us to discuss what we would change about school. While some at my table wished for a later start time or more STEM (or even better coffee in the teachers’ lounge), I wished that I could scrap the whole system where students move to the next grade at the beginning of the new school year. I wish that students moved to the next classroom when they had mastered the skills, no matter how long it took. I may not be able to totally rework the traditional school system, but I can rework the writing instruction in my class.